The virtual and its effect on social relations/ The impact of hyperconnectivity on sociality:

An exploration of social isolation and the collective experience of music IRL.

(working title)

This blog forms part of the visual and inventive research for my MA Visual Sociology dissertation, which I am planning to hand in in autumn 2020. Due to the current Coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing lockdowns, we are forced to stay indoors all over the world; and, as such, my research will have to be carried out here, online, rather than IRL [In Real Life]. I will be sharing the inspirations I discover for my topic, which has changed a little bit during the outbreak of the virus. In order to prevent self-plagiarism, I will try to only share pictures and quotes from relevant research and not much written text. The written text will be my dissertation, which will come after the online research process. This blog facilitates the archiving of what inspires the topic on a daily basis. Additionally, its online format allows me to get in touch with possible participants without leaving the house, thus practicing social distancing. I, in no way, expect readers to read all of what is on here, as it would be an endless scroll. This in itself becomes a way to address the endless scroll some of us partake in for so many hours of our days on our ‘social’ media pages or other sites online.

Keywords: face-to-face, social, smartphone, anxiety, isolation, body, music, singing, ecstatic, ecstasy

[I would recommend using the search function on your keyboard, shift/ caps lock + cmd + F, to click yourself through this body of text via the listed keywords.]

Prior to the outbreak of the virus, my dissertation was going to be entitled, “The virtual and its effect on our social relations: In what ways are smartphone users in Western Europe disconnected from their bodies?” The visual and inventive method I was going to use to explore the feeling of social isolation (and ultimately transform it into an empowering feeling of community) was the embodied operatic, collective experience of singing in a choir.

Now, in the midst of the virus and the attempts to contain it, I aim to rethink title and topic with the newly introduced expressions self-isolation and social distancing in mind.

The main focus of my research is on the increased use of smartphones, and other smart devices, as the main cause for social isolation. Often smartphones function as substitutes for face-to-face encounters. My thesis is that the more we use smartphones, instead of being with other people IRL, the more alienated and isolated we get from each other.

Before the endless scroll of collected quotes and other relevant media begins and swallows you whole, just the remark that the direction and, thus, wording of the title might change throughout the research process. With this blog I will be examining how my dissertation topic might change in the light of the virus enforcing isolation and, inevitably, shifting work, entertainment and socials from IRL (from the real) to the virtual.

“One consequence of communicating via text online, therefore, is that it can reduce people’s understanding of others’ thoughts and feelings (compared to communicating in speech offline), provoking possible miscommunication. Another consequence is that losing access to vocal paralinguistic cues can reduce feelings of social connection.” (Lieberman and Schroeder, 2020: 17)

“Online environments—which cater to anonymity and weakened social norms—may serve as a breeding ground for such behaviors [14,15]. Indeed, recent research suggests that social media can serve as a catalyst for moral outrage and social conflict [16, 17].” (Ibid.)

“Connecting with someone online (e.g. following or friending a celebrity) provides fertile ground to form para social relationships (one-sided psychological relationships).” (Ibid., 18)

“Despite the many differences in the structure and psychology of online and offline communication, these interactions often bleed into one another. A person may interact with a friend via social media one minute and then see her in person the next. We document ways in which online interaction can (1) disrupt or (2) enhance offline interaction.” (Ibid.)

“The mere presence of having one’s smartphone is distracting (e.g. [40]) and can reduce the effectiveness of offline connection. Phone use during social interaction can reduce feelings of social connection [41,42,43,44], the perceived quality of the interaction [45,46], enjoyment gained from the interaction [47], and even frequency of smiling at others [48].” (Ibid.)

“As another example, individuals assigned to navigate to a new location using their smartphone (versus no phone) were able to find the location more easily but also felt less socially connected [42]. Further, feeling snubbed as a result of someone else using a phone during a face-to-face interaction (‘phubbed’) can lead to feelings of social exclusion and increase motivation to seek out social connection other ways, such as online [41].” (Ibid.)

“Other forms of online engagement, such as taking photos, can impact offline experiences as well. Specifically, when taking photos increases experiential engagement, it can enhance enjoyment [49], but taking photos with the intention of sharing them can increase self-presentation concerns and thus decrease experiential engagement and subsequent enjoyment [50]. Digital technology can also disrupt social connection depending on the way it is used. Online interaction can harm well-being and reduce sociality if it displaces in-person connections [51,52,53,54]. Further, the passive use of social media, in particular (e.g. lurking behaviors; scrolling through others’ feeds without actually engaging), has been associated with increased loneliness and lowered well-being [51,52,53,54,55].” (Ibid.)

“The recent shift from offline to online interactions has fundamentally changed the way humans socialize and communicate, creating controversy about the impact of digital technology on well-being [63,64,65]. This paper provides a new framework for organizing the extant literature. The consequences of digital technology can be categorized based on the structural differences between online (versus offline) platforms—fewer nonverbal cues, more anonymity, more flexible network selection, and wider audience—and the ways in which technologies harm or enhance offline connection.“ (Ibid.)

“Our framework also identifies many remaining research questions. Here we highlight some of the most ambitious questions that future work could pursue. First, if online interactions increase misunderstanding and dehumanization (because they lack nonverbal cues), how might different communication technologies reduce civility and increase conflict more broadly?” (Ibid.)

“Online gamers will soon be able to select customizable voices, allowing them to choose how they sound while maintaining their own vocal inflection, simultaneously increasing both realism and anonymity [66].“ (Ibid.)

“The future of human sociality lies in understanding, and consequently shaping, online interaction. It is more important than ever for science to maintain pace with this social evolution.” (Ibid., 19)

REFERENCE: Lieberman, A. and Schroeder, J. (2020). Two social lives: How differences between online and offline interaction influence social outcomes. Current Opinion in Psychology, 31, 16-21. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352250X1930065X [Accessed 18 March 2020].

“Technology is seductive when what it offers meets our human vulnerabilities. And as it turns out, we are very vulnerable indeed. We are lonely but fearful of intimacy. Digital connections offer the illusion of companionship without the demands of friendship.” (Turkle, 2011: 1)

REFERENCE: Turkle, S. (2011). Alone together: Why We Expect More From Technology And Less From Each Other, New York: Basic Books.

“Why do so many of us prefer simulated relationships to real ones? Is reliance on technology altering what it means to be human?“ (Behr, 2011)

“The test is one of many cited by Sherry Turkle in Alone Together as evidence that humanity is nearing a “robotic moment”. We already filter companionship through machines; the next stage, she says, is to accept machines as companions. Soon, robots will be employed in “caring” roles, entertaining children or nursing the elderly, filling gaps in the social fabric left where the threads of community have frayed. Meanwhile, real-world interactions are becoming onerous. Flesh-and-blood people with their untidy impulses are unreliable, a source of stress, best organised through digital interfaces – BlackBerries, iPads, Facebook. […] Turkle has interviewed people of all ages and from a wide range of social backgrounds and finds identical patterns of compulsive behaviour. We start with the illusion that technology will give us control and end up controlled. We get Blackberries to better manage our email, but find ourselves cradling them in bed first thing in the morning and last thing at night.” (Ibid.)

“Turkle interviews teenagers who are morbidly afraid of the telephone. They find its immediacy and unpredictability upsetting. A phone call in “real time” requires spontaneous performance; it is “live”. Text messages and Facebook posts can be honed to create the illusion of spontaneity.” (Ibid.)

“This digital generation also expects everything to be recorded. In any social situation, there are phones with cameras that relay personal triumphs and humiliations straight to the web. Turkle’s interviews debunk the myth that web-savvy kids don’t care about privacy. Rather, they see it as a lost cause. The social obligation to be part of the network is too strong even for those who resent the endless exposure. Teenagers perform on the digital stage, suppressing anxiety about who is lurking in the audience.” (Ibid.)

“From that anxiety flows ever greater reliance on technology to mediate human relations. Human beings can be needy, capricious, threatening, but at least calls can be diverted, emails blocked, Facebook friends “unfriended”. Turkle sees this too as a symptom of incipient roboticism. The network encourages narcissism, teaching us to think of other people as a problem to be managed or a resource to be exploited.” (Ibid.)

REFERENCE: Behr, R. (2011). Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other by Sherry Turkle – review. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/jan/30/alone-together-sherry-turkle-review (Acccessed: 18February2020)

“Consider the apparently benign game Pokémon Go, both a ridiculous and a transparent example of the link between behavioural surplus [The totality of information about our every thought, word and deed, which could be traded for profit in new markets based on predicting our every need – or producing it.] and physical control. While its initial players lauded the game for its incitement to head outside into the “real world”, they in fact stumbled straight into an entirely fabricated reality, one based on years of conditioning human motivation through reward systems, and designed to herd its users towards commercial opportunities. Within days of the game’s launch in 2016, its creators revealed that attractive virtual locations were for sale to the highest bidder, inking profitable deals with McDonald’s, Starbucks and others to direct Pokémon hunters to their front doors. The players think they are playing one game – collecting Pokémon – while they are in fact playing an entirely different one, in which the board is invisible but they are the pawns. And Pokémon Go is but one tiny probe extending out from Google and others’ vast capabilities to tune and manipulate human action at scale: a global means of behaviour modification entirely owned and operated by private enterprise.” (Bridle, 2019).

REFERENCE: Bridle, J. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff review – we are the pawns. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/feb/02/age-of-surveillance-capitalism-shoshana-zuboff-review [Accessed 24 January 2020].

“Preoccupation with our cellphones has irrevocably changed how we interact with others. Despite many advantages of smartphones, they may undermine both our in-person relationships and our well-being. As the first to investigate the impact of phubbing (phone-snubbing), the present research contributes to our nascent understanding of the role of smartphones in consumer behavior and well-being. We demonstrate the harmful effects of phubbing, revealing that phubbed individuals experience a sense of social exclusion, which leads to a heightened need for attention and results in individuals attaching to social media in hopes of regaining a sense of inclusion. Although the stated purpose of technology like smartphones is to help us connect with others, in this particular instance, it does not. Ironically, the very technology that was designed to bring humans closer together has isolated us from these very same people.

Our preoccupation with technology, smartphones in particular, has irrevocably changed how we interact with others. Despite the many advantages afforded by the portability and multifunctionality of the modern smartphone, our current obsession with smartphones comes at a cost to our real, in-person relationships. Several researchers (Mick and Fournier 1998; Lang and Jarvenpaa 2005; Turkle 2011) have observed that the near-universal availability and ever- expanding capabilities of the smartphone have led to two paradoxes: (1) the present-absent paradox (alone together) and the (2) freeing-enslaving paradox. Both of these paradoxes address how we communicate and relate with others.” (David and Roberts, 2017: 155)

“In the present-absent paradox, we are physically present for others but are really absent, preoccupied with our smartphones.” (Ibid.)

“In the freeing-enslaving paradox, smartphones allow us the freedom to communicate with others, be entertained, work from remote locations, and access information in ways undreamed of a mere 20 years ago. This freedom, however, comes at a cost. Being always on and constantly available brings with it a sense of responsibility, or even obligation, to respond in a timely fashion to our technology. We live in a world of constant distraction. The present research investigates how such distraction caused by our smartphones can negatively affect others. Specifically, our study focuses on “phone snubbing” and its impact on consumers.“ (Ibid.)

“Phubbing is a portmanteau of the words “phone” and “snubbing.” To be phubbed is “to be snubbed by someone using their cellphone when in your company.” (Roberts and David, 2016: 134).

“The omnipresent nature of smartphones makes phubbing an inevitable occurrence.” (Ibid.)

REFERENCE: Roberts, J. and David, M. E. (2016). My life has become a major distraction from my cell phone: Partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction among romantic partners. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 134-141.

All of this research, mostly derived from the field of Psychology, so far confirms that there is a link between smartphone use and social isolation. I am interested in this topic because I, myself, am at times avoiding face-to-face encounters. I prefer the control I have in a conversation online; I find it hard to undo this reflex and I was thinking of ways to “re-teach” collectivism and “re-teach” community. One method I came up with is the collective experience of music. In fact, the paraphrasing of Nietzsche by Bettany Hughes on BBC has inspired me the most. Here are some notes I took while watching the documentary:

Wagner’s theory where art could transform society.

Visceral stories of human suffering in greek stories. Dancing, wildness, the visceral feelings. Tragedy. Dionysus.

Nietzsche says that the individual somehow lost themselves in the collective, and found in a group experience an ecstatic transformational experience. He saw it in Wagner’s music and in the tragedy, so that somehow the suffering that was everybody’s condition was transformed through this ecstatic experience into an affirmation of life, this life, here and now. Like a rock concert! Lose yourself in this great ecstatic, collective experience.

So, my aim was to not only make research about social isolation and internet use, but to research ways in which the body can become the centre of our activities again rather than the mind.

The materialist turn in social sciences: This turn to materiality is rooted in a critique of the privileging of mind over matter. “This turn to matter, marked by a spate of attention to physical materiality within the humanities, opens doors for new types of interdisciplinarity and new resources for knowing our nature-cultural worlds, to borrow Haraway’s (2003) influential turn of phrase (Mamo and Fishman 2013; Papoulias and Callard 2010). In so doing, it promises to inaugurate a radical paradigm shift in how we understand the social.” (Willey, Pollock and Subramaniam, 2016: 993)

REFERENCE: Willey, A., Pollock, A., and Subramaniam, B. (2016). A World of Materialisms: Postcolonial Feminist Science Studies and the New Natural. Science, Technology, & Human Values,41(6), 991-1014.

“As information becomes the fundamental commodity of this new economy, physical activity is being elbowed out of our work lives.” (Cregan-Reid, 2019)

TRIGGER WARNING: The following quote might be distressing for those who are, in this vulnerable time, worried about what self-isolation might do to their health. It describes the impact of staying indoors and the use of technology on the human body. Still, staying indoors and using technology are the only two things most of us do in this time. Not to forget that health is a major global concern; we are afraid of contracting the deadly new coronavirus and of infecting others.

“And so the tectonic creep of technology, which brings with it more indoor habits, is changing our bodies, too. Indoor time, which provides poor quality light with no opportunity for our skin to make vitamin D, is also strongly associated with the global epidemic of myopia. It’s currently estimated that if nothing is done to curb the trend, half the world’s population will be shortsighted by 2050 – and about 2.5 per cent of people with high myopia go blind in older age. ‘The English Disease’ is making a comeback, and vitamin D deficiency has also been linked with the steep rise in food and nut allergy.” (Ibid.)

“Modern life is driving too many of our pathologies to list, and they are not rare. Everything from asthma and ADHD to flat feet and types 1 and 2 diabetes are among them. The number one cause of global disability is back pain; it is strongly associated with sedentary life. And as information technology extends our working days and stresses us out, the masseter muscles that grind our teeth in our sleep widen our jaw as they get their nightly workout.” (Ibid.)

“Inactivity, driven especially by chair use and technology, plays a role in tens of millions of global deaths each year. Seven of ten of the World Health Organization’s biggest killers are associated with inactivity. The top two are heart disease and stroke and, claiming 17 million lives each year, these alone outnumber the other eight in the list.The world of work has changed so many times, and with it, so have our bodies. The internet has remodelled us by changing the ways that we work. Over time, the variety of work has homogenised so completely that the physical labour performed by an investment banker turning over multi-milliondollar deals is indistinguishable from that of a child doing homework.”(Ibid.)

REFERENCE: Cregan-Reid, V. (2019). What is the internet doing to our bodies? Available at: http://sites.barbican.org.uk/liferewired-vybarrcreganreid/ [Accessed 20 March 20].

Above you can read what the use of smartphones actually does to our bodies. New expressions, such as HOLS (Hunched Over Laptop Syndrome) and “iPad Neck” explain new ailments caused by looking at screens all day – at work and at home. Mark Fisher speaks of students [at Goldsmiths College] that “will be found slumped on desk, talking almost constantly, snacking incessantly (or even, on occasions, eating full meals). (Fisher, 2008: 23). “What we are facing here is not just time-honored teenage torpor, but the mismatch between a post-literate ‘New Flesh’ that is ‘too wired to concentrate’ and the confining conceptual logics of decaying disciplinary systems. To be bored simply means to be removed from the communicative sensation-stimulus matrix of texting, YouTube and fast food; to be denied, for a moment, the constant flow of sugary gratification on demand. […] pop is experienced not as something which could have impacts upon public space, but as a retreat into private ‘OedIpod’ consumer bliss, a walling up against the social.” (Ibid., 24) This was in 2008. Instagram was founded 2 years later.

REFERENCE: Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist realism is there no alternative? Winchester: O Books.

“BY FALL 2019 I came to understand Instagram dwellers as broken people — my people. If I was getting depressed, so was everyone else. The algorithm’s hall-of-mirrors effect seemed to be at work again: more and more people were posting about staying in, struggling with their mental health, and finding a community of fellow sufferers on the platform. But it wasn’t just me and my algorithm. Other people were growing disenchanted and reclusive, and think pieces confirmed the trend. Tavi Gevinson published a New York magazine cover story chronicling her ambivalence about growing up on Instagram. The Atlantic claimed “The New Instagram It Girl Spends All Her Time Alone” and described how influencers were staging more selfies at home to appear relatable to their followers. Home-delivery services, loungewear brands, and weighted-blanket manufacturers were all well poised to capitalize.” (Tortorici, 2020)

REFERENCE: Tortorici, D. (2020). My instagram. We all die immediately of a Brazilian Butt Lift. nplusonemag.com. Available at: https://nplusonemag.com/issue-36/essays/my-instagram/ [Accessed 18 March 2020].

“Contradictory consciousness-management has superseded social anxiety about Bad Faith. This has long been the thesis of Slavoj Žižek. Let’s work on this thesis and take seriously the cynical statement “They know what they do, but they do it anyway” and apply this to social media. There is no longer a need to investigate the potential of “new media” and deconstruct their intentions. The internet has reached its hegemonic stage. In previous decades it was premature to associate intensive 24/7 usage by millions with deep structures such as the (sub)conscious. Now that we live fully in social media times, it has become pertinent to do precisely that: link techne with psyche.” (Lovink, 2016)

“Under this spell of desire for the social, led by the views and opinions of our immediate social circle, our daily routines are as follows: view recent stories first, fine-tune filter preferences, jump to first unread, update your life with events, clear and refresh all, not now, save links to read for later, see full conversation, mute your ex, set up a secret board, run a poll, comment through the social plug-in, add video to your profile, choose between love, haha, wow, sad, and angry, engage with those who mention you while tracking the changes in relationship status of others, follow a key opinion leader, receive notifications, create a photo spread that links to your avatar, repost a photo, get lost in the double-barrel river of your timeline, prevent friends from seeing updates, check out something based on a recommendation, customize cover images, create “must-click” headlines, chat with a friend while noticing that “1,326,595 people like this topic.” (Ibid.)

“Academic internet studies circles have shifted their attention from utopian promises, impulses, and critiques to “mapping” the network’s impact. From digital humanities to data science we see a shift in network-oriented inquiry from Whether and Why, What and Who, to (merely) How. From a sociality of causes to a sociality of net effects.” (Ibid.)

“We have long come to terms with the actual and virtual nature of the social, as its potential for play and manipulation seems increasingly in abeyance. Social media demand from us that we perform in a never-ending show. We keep coming back, always remaining logged in, until the #DigitalDetox sets in and we’re called to different realms.” (Ibid.)

“We all remain stuck in the social media mud, and it’s time to ask why.” (Ibid.)

“Why is updating such a seductive yet boring habit?” (Ibid.)

“What remains particularly unexplained is the apparent paradox between the hyper-individualized subject and the herd mentality of the social. What’s wrong with the social? What’s right with it?” (Ibid.)

“When it comes to social media we have an “enlightened false consciousness” in which we know very well what we are doing when we are fully sucked in, but we do it anyway.” (Ibid.)

“We’re all aware of the algorithmic manipulations of Facebook’s news feed, the filter-bubble effect in apps, and the persuasive presence of personalized advertisement. We pull in updates, 24/7, in a real-time global economy of interdependencies, having been taught to read news feeds as interpersonal indicators of the planetary condition.” (Ibid.)

“It’s definitely harder to avoid social media than it is to give into it. Most people tend to give into it, because its easier” (Adele).” (Ibid.)

“In an age of installed, micro-perceptual effects and streamed programming, ideology does not merely refer to an abstract sphere where the battle of ideas is being fought. Think more in line with a Spinozan sense of embodiment—from the repetitive strains of Tinder swiping, to text neck, to the hunched-over-laptop syndrome.” (Ibid.)

“”What are you doing?” said Twitter’s original phrase. The question marks the material roots of social media. Social media platforms have never asked “What are you thinking?” Or dreaming, for that matter. Twentieth-century libraries are full of novels, diaries, comic strips, and films in which people expressed what they were thinking. In the age of social media we seem to confess less what we think. It’s considered too risky, too private. We share what we do, and see, in a staged manner. Yes, we share judgments and opinions, but no thoughts. Our Self is too busy for that, always on the move, flexible, open, sporty, sexy, and always ready to connect and express.” (Ibid.)

“With 24/7 social visibility, apparatus and application become one in the body. This is a reversal of Marshall McLuhan’s Extensions of Man—we are now witnessing an Inversion of Man. Once technology entangles our senses and gets under our skin, distance collapses and we no longer have any sense that we are bridging distances. With Jean Baudrillard we could speak of an implosion of the social into the hand-held device in which an unprecedented accumulation of storage capacity, computational power, software, and social capital is crystallized. Things get right in our face, our ears, steered by our autonomous finger tips. This is what Michel Serres admires so much in the navigational plasticity of the mobile generation, the smoothness of its gestures, symbolized in the speed of the thumb, sending updates in seconds, mastering mini-conversations, grasping the mood of a global tribe in an instant. To stay within the French realm of references: social media as the apparatus of sexy and sporty “active acting” makes it a perfect vehicle for the literature of despair epitomized by Michel Houellebecq’s messy body(-politics).” (Ibid.)

“The illusion with which the user surrounds him- or herself while swiping and tapping through social media updates feels natural and self-evident for the very first time. There is no steep learning curve or rite of passage; we need not shed blood, sweat, and tears to fight our way into the social hierarchy. From day one the network configuration makes us feel at home, as if WhatsApp, QQ, and Telegram have always existed. Down the line, however, this immediate familiarity becomes the main source of discontent. We’re no longer playing, like in the good old days of LamdaMOO and Second Life. Intuitively, we sense that social media constitute an arena of struggle where we display our “experientialism” (James Wallman), where hierarchy is a given, and profile details such as gender, race, age, and class are not merely “data” but decisive measures in the social stratification ladder.” (Ibid.)

“Social media’s imaginary community that we stumble into (and leave behind the moment we log out) is not fake. The platform is not a simulacrum of the social. Social media do not “mask” the real. Neither the software nor the interface of social media are ironic, multilayered, or complex. In that sense, social media are no longer (or not yet) postmodern. The paradoxes at work here are not playful. The applications do not appear to us as absurd, let alone Dada. They are self-evident, functional, even slightly boring. What attracts us is the social, the never-ending flow, and not the performativity of the interfaces themselves. (Performativity seems to be the main draw of virtual reality, now in its second hype cycle, twenty-five years after its first).” (Ibid.)

“Let’s appraise the bots and the like economy for what they are: key features of platform capitalism aimed at capturing value behind the backs of their users. Social media are a matter of neither taste nor lifestyle, in the sense of “consumer choice.” They are our technological mode of the social.””(Ibid.)

REFERENCE: Lovink, G. (2016). On the Social Media Ideology. Journal #75. e-flux. Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/75/67166/on-the-social-media-ideology/ [Accessed 18 March 2020].

“Julie Cohen (2012), for instance, criticises the poststructuralist notion of the disembodied multiple self in cyberspace. The conception of cyberspace as a separate, alternative world is blind to material inequalities and their digital continuations. Instead, Cohen claims, digital space is intertwined with analogue space. Both are perceptible only through the organic body. Jessica Brophy (Brophy, 2010, p.932) adds that online communication is based on material prerequisites: the body, its physical and cognitive capabilities, the material infrastructure (hardware), and financial resources (digital divide). By adding perspectives from cognitive science (positivist inspirations) to ideas of discursive and performative creation of space (poststructuralist inspirations), Cohen explains space as the result of embodied perception. Images, sound, and smell are ordered in relation to the specific location of the individual subject. Cognition, and thus the knowledge of space, is radically relational. It is perceived differently from each perspective and through each body.” (Asenbaum, 2019: 13)

“Technological change, Cohen goes on to argue, alters embodied perceptions of reality. Just as the use of automobiles alters the relations of time and space, so does digital communication. These new perspectives affect not just the perception of reality online, but also the perception of reality in analogue society at large. The digital subject thus does not consist merely of a digital body, but also of the reconfigured physical body, which it perceives differently through the digital. This is even more true in the age of the Internet of Things, in which digital communication is mediated not only through single, immobile computer screens but through numerous mobile devices, multiplying interfaces around the subject: Data flows escape the obvious bounds of the networked computer and cross into and out of homes, cars, personal accessories, and public spaces by many avenues… Networked space is neither empty nor abstract, and is certainly not separate; it is a network of connections wrapped around every artefact and human being. (Cohen, 2012, p.46).” (Ibid., 14)

“Today’s discussions incorporate new technological developments such as the Internet of Things and broadband connections, which are identified as the prime reason for the emergence of new digital corporealities (Daniels, 2009; Gies, 2008).” (Ibid.)

“If we understand ourselves as assemblages of agentic things that relate our physical bodies including their bloodstreams, hormones, bones, sex organs, and skin pigmentations to culturally-coded objects such as makeup, clothing, and hairstyle and to the discursive identity concepts of class, race, and gender, then we can see how digital objects entering these assemblages reconfigure our selves. The early cyborgian theories of Haraway and Turkle are actualized by considering how digital objects of self-representation become part of human identity assemblages. Thus, not only do humans create computers, but computers and their algorithmic logics co-create us.” (Ibid., 20).

REFERENCE: Asenbaum, H. (2019). Rethinking Digital Democracy: From the Disembodied Discursive Self to New Materialist Corporealities. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337490063_Rethinking_Digital_Democracy_From_the_Disembodied_Discursive_Self_to_New_Materialist_Corporealities [Accessed 18 February 2020].

To bring the body back into our lives, despite of living in the digital era, and to examine how this can be done, was the aim of my visual sociology project. I was interested in the collective, ecstatic experience of the operatic choir or the chorus of the tragedy.

Now, a global tragedy has occurred, that has transformed all of our lives dramatically. All over the world, people are at risk for contracting the deadly new Coronavirus. There is no cure and there are only limited hospital beds in each country. The only way to deal with this pandemic right now is for everyone to stay indoors, to self-isolate and to practice social distancing to prevent more infections. In a world, where the governments strongly advice their citizens to stay apart from each other, a sociology project about reconnecting to one’s body and being with other people IRL is hard to pursue. However, this crisis can remind us of how precious the body and community are. It already reminds us of the vulnerability of our bodies, of our mortality and thus of the importance of living the life we have in and with our bodies and not like zombies glued to our phones.

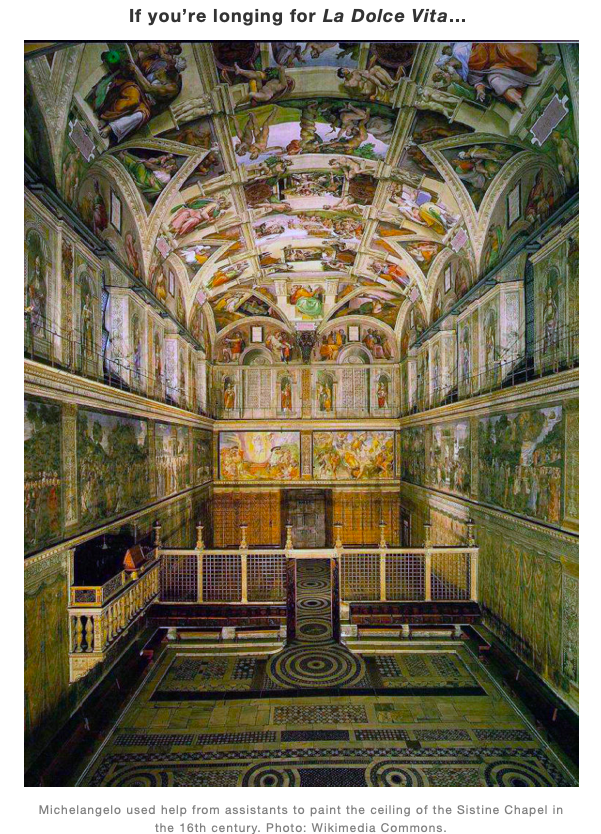

Meanwhile on Italy’s balconies, operatic voices join into a chorus, bridging distances and reaching neighbours, to overcome feelings of longing and isolation.

“[…] a chorus of people who have been transformed, who have completely forgotten their past as citizens, their social position: they have become the timeless servants of their god, living outside all spheres of society. […] Following this insight, we must understand Greek tragedy as the Dionysian chorus which again and again discharges itself in an Apollonian world of images. So those chorus parts which are interwoven through tragedy are to a certain extent the maternal womb of the whole so-called dialogue, that is, of the whole world of the stage, of the real drama. In several successive discharges, this original ground of tragedy radiates that vision of drama: which is thoroughly dream-phenomenon and to that extent of an epic nature, but on the other hand, as objectivation of a Dionysian state, represents not the Apollonian redemption in appearance, but on the contrary the shattering of the individual and his union with the original being.” (Nietzsche, 2008: 50 f)

“This view of ours offers a full explanation of the chrous of Greek tragedy, the symbol of the whole mass in Dionysian arousal. While we, accustomed to the place of the chorus on the modern stage, and especially of the opera chorus, could not understand how the Greek tragic chorus should be older, more original, even more important than the real ‘action’ – as this was yet so clearly transmitted by the tradition – while we in turn could not reconcile that great importance and originality as outlined in the tradition with the fact that the chorus was composed exclusively of lowly servant beings, even, in the first place, of goat-like-satyrs, while the orchestra in front of the stage remained a constant enigma to us, we arrived at the insight that the stage together with the action was basically and originally conceived only as a vision, that the sole ‘reality’ is precisely the chorus, which produces the vision from itself and speaks of it with the whole symbolism of dance, music, and word.” (Ibid., 51)

“[…] the chorus is the highest, indeed Dionysian expression, of nature and speaks therefore, like nature, oracular words of wisdom in a state of enthusiastic excitement: as the compassionate chorus, it is at the same time the wise chorus, proclaiming the truth from the heart of the world.” (Ibid.)

REFERENCE: Nietzsche, F., and Smith, D. (2008). The birth of tragedy (Oxford world’s classics (Oxford University Press)). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

“Classical Greek Tragedy.

Ancient Greece invented drama. Drama grew out of festivals honoring Dionysus—included performances by choruses (troupes of dancers who would chant and sing).” (Leeke, 2017)

“Greek Theater. The Greek theater is the predecessor of the current day “amphitheater.” Built in the open, usually on the side of a hill. Large, could usually accommodate as many as 15,000 spectators basic shape was circular.” (Ibid.)

“Greek Tragedy Best definition was by Aristotle in Poetics.

Downfall of a character who is neither completely good nor completely bad. Fall brought about by a tragic flaw. Witnessing the downfall of basically good people evoked emotions of pity and fear in the audience. Audience then experiences a catharsis or some sort of emotional cleansing.” (Ibid.)

“8 Characteristics of Tragedy

1. The hero (protagonist) is a person of high estate who must be good and have good intentions. The hero must also be true to life. 2. The hero has a hamartia, fatal or tragic flaw, an error or frailty; usually hubris— excessive human pride, arrogance. 3. The hero suffers a reversal of fortunes. 4. No universal questions are raised; fate is accepted as inevitable when it becomes apparent; no debate is held with the gods. 5. The gods are capricious; often enemies of the hero and are never loving or righteous. No justice can be expected from the gods. 6. A full chorus is present and gives advice. The chorus reflects opinions of the townspeople. 7. A complicated plot is present along with cataclysmic events; however, all violent actions take place off stage and are reported to the audience by witnesses. 8. Hero suffers a great and permanent fall with no hope. The story ends in despair and evokes both pity and fear in the audience.” (Ibid.)

“Function of the Chorus. 1. Represents members of population or townspeople and converses with or gives advice to characters. The chorus is involved in or affected by the action of the play. 2. Serves as commentators on events, interprets events, and gives background of preceding events. 3. Chants odes between episodes of play. Often the singing is accompanied by stately dance movements to the left and to the right which contributed beauty to the play. 4. Relieves tension Examples: Mamma Mia! and Hercules.” (Ibid.)

REFERENCE: Leeke, A. (2017). Classical Greek Tragedy. Available at: https://slideplayer.com/slide/4155606/ [Accessed 1 April 2020].

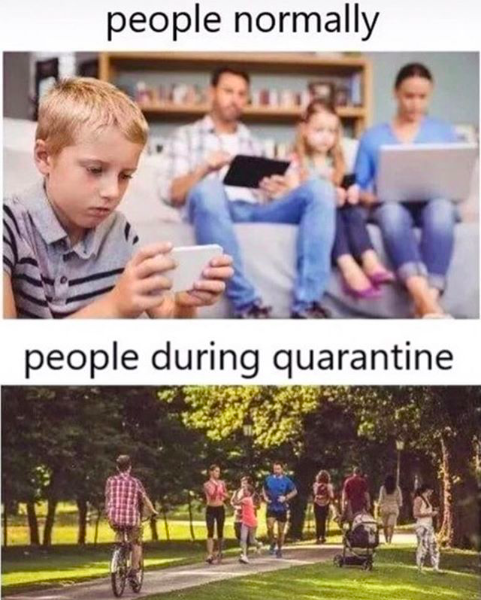

I walked to the park today to get some fresh air – with my mouth covered and disinfectant wipes in my bag. When I got to the park, I saw something I never normally see (partly because on Sundays I stay indoors and watch Netflix): it was packed with people of all ages (mostly in their twenties), who were actively engaging with their physical surroundings, who were physically and mentally in the same place, connecting to nature and the world around them. They didn’t look on their phones or rushed through, but sat down and breathed in the fresh air, read a book or walked around and inspected what the park had to offer (ducks, descriptions of plants, etc.) – all in save distance to others. It was a new vision and a somber mood.

Although we are told to stay at home, going to the park seems like an acceptable thing to do, considering being outside strengthens one’s immune system and the two metre distance rule can be abided. It might be the only chance for a walk outside before the UK, like Italy, France and Spain, is under complete lockdown. What I am trying to say is that many of us were distant before the pandemic, many of us stayed indoors before the pandemic and many of us did not look at their surroundings before the pandemic. It seems that what it takes to have people connect IRL, is the prohibition from going outside and meeting friends. The saying applies here: It’s only when you lose something, that you realise how much you miss it.

For the time being, phones and laptops are the only devices one has while self-isolating to get into contact with others without leaving the house. (I realise that this is coming from a privileged place.) It is lonely, but weren’t we lonely before? Now, at least, we know that everyone has to be alone at home and it’s the same rule for everyone. So, although we now have to be physically apart there is a feeling of togetherness.

Imagining a post-Covid-19 world together.” Available at: https://www.instagram.com/self_isolation_residency/?hl=de.

I will continue this blog with uploading currently circulating pictures and articles that I came across on social media and the online news in the endless scroll of trying to gather information from my bedroom about the pandemic outside.

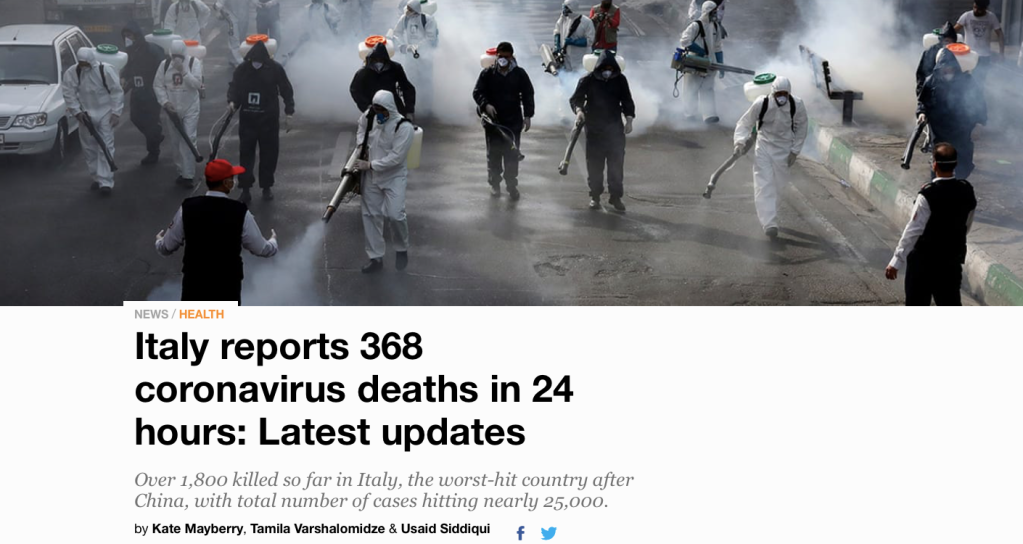

As Italy is hit the worst after China by Covid-19, the country, especially the north of the country has been under lockdown for some time now, with the number of deaths rising daily. There have been videos and pictures of Italians singing and making music from their balconies to communicate with each other despite of being physically apart. People did so to support each other and remind each other that they were not alone and that they were in this together. [If any Italians (who are under lockdown at the moment or otherwise) want to comment on this, please do so.] Seeing those videos touched a lot of people around the world.

“In a world dominated by the visual, could contemporary resistances be auditory?”

REFERENCE: description of LaBelle’s “Sonic Agency” (2018). Available at: https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/sonic-agency [Accessed 19 March 2020].

Now that the visual (of people, movement, life) is removed from the public , the audio (singing and making music together) has become a way of coping with being physically apart from each other. It’s an emotional act of yearning to go back to normal, to be together without risking lives and a reminder that we are all in this together. Despite of the previously lived desire for individualism, we have a mob mentality online; we are online to connect with others. Some might have substituted their real life connections with “connections” online. Now that being online is one of the only (safe) ways to be with others, we might miss meeting each other IRL. It is the choice to go out and meet other people that we no longer have. We might have spent most of our time alone and in our flats before, but we still had the choice to go out. To do a research project about social isolation caused partly by smartphone use with the aim to teach us to refrain from using smartphones to connect and instead connect in person, seems contradictory to the fact that the internet is one of the only ways we can get “in touch” with each other. Not to forget that the internet enables people to connect and share information globally, past closed borders. The Italians who are in quarantine are teaching us that singing and making music from balconies together is another way to connect with each other. That way even allows us to be fully present, with our mind and our body.

“Our research contributes to the extant literature by identifying and testing one path through which individuals become attached, if not addicted, to social media. It may not be out of boredom or a desire to be entertained that so many people spend so much time on Facebook or other social media; instead, it may be that the time spent on social media is a pointed attempt to (re)gain community in a world that, paradoxically, is becoming increasingly alienated (Putnam 2000).” (David and Roberts, 2017: 156)

“Being a part of social groups is an innate desire of humans (Baumeister and Tice 1990; Mead et al. 2011; Lee and Shrum 2012), and such a desire will lead “phubbed” individuals to search elsewhere for a sense of belonging (Han, Min, and Lee 2015). In an increasingly technology-driven society, it is critical that investigation continue into how the use of such technology is affecting how we relate to one another. Indeed, and consistent with the present-absent paradox discussed above, it may be that attachment to social media and connectedness with our phones is slowly deteriorating real in-person connections.” (Ibid., 159)

“Upon social exclusion, our desire to rebalance a sense of inclusion is immediately activated.” (Ibid.)

“Research has found that a Facebook “Like,” posting a photo or comment, or the familiar ring of a notification releases dopamine similar to the rush we might get from an in-person hug or smile (Soat 2015).” (Ibid.)

“Individuals from all age groups are spending an increasing amount of time interacting with their cell phones and less and less time interacting with their fellow humans (Pew Internet 2014; Wall Street Journal 2015). Although cell phones provide tremendous opportunities for connectivity with others, recent research suggests that increased connectivity with cell phones may occur at the detriment of human interaction (McDaniel and Coyne 2014; Roberts and David 2016).” (Ibid., 160)

REFERENCE: David E. Meredith and Roberts, J. A. (2017). Phubbed and Alone: Phone Snubbing, Social Exclusion, and Attachment to Social Media. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, vol. 2, issue 2, 155-163.

“A major paradox arises about digitally mediated social connection; we need solitude in order to connect, or we need to (temporarily) neglect those physically around us to offer our attention to those absent. Turkle notes that, “being alone can start to seem like a precondition for being together because it is easier to communicate if you can focus, without interruption, on your screen.” She asks, “What is a place if those who are physically present have their attention on the absent?”” (Genner, 2017: 71)

What is a place if those who are physically present have their attention on the presence?

I really recommend Sarah Genner’s empirical work on hyperconnectivity from 2017, which was accepted as a PhD thesis by the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Zurich in the spring semester 2016.. It’s a very detailed work on the risks and rewards of the “anytime-anywhere internet”, hence it’s 197 pages. If you are interested it might give you something to do in your self-isolation (I am not through yet, so it’s definitely on my to do list). I’m inserting the table of contents below for you to get a taste of the range of topics that can be discussed in studies of the internet:

“Douglas Rushkoff argues that with real-time technologies such as Twitter and email, we have arrived in the age of the “present shock.” Rushkoff describes the Internet as an instantaneous network where time and space get compressed. He argues that there is a

dissonance between our digital selves and our analog bodies, which has thrown us into a new state of anxiety. (Rushkoff, 2013)“. (Genner, 2017: 25)

REFERENCE: Genner, Sarah. (2017). ON |OFF : Risks and rewards of the anytime-anywhere internet. Available at: https://digitalcollection.zhaw.ch/handle/11475/1857 [Accessed 19 March 2020].

The above quotes confirm that the online/offline dualism can cause anxiety. This project is looking for participants who relate to this statement. As part of my methodology, I will create pictures with fictive texts, known as vignettes, that will help me find participants. Below is some information on vignettes as a methodology:

“Vignettes can be useful in exploring potentially sensitive topics that participants might otherwise find difficult to discuss (Neale 1999). As commenting on a story is less personal than talking about direct experience, it is often viewed by participants as being less threatening. Vignettes also provide the opportunity for participants to have greater control over the interaction by enabling them to determine at what stage, if at all, they introduce their own experiences to illuminate their abstract responses.” (Barter and Renold, 1999)

“For many researchers the indeterminate relationship between beliefs and actions is the biggest danger in using this technique in isolation (West 1982, cited in Finch 1987; Faia 1979). If the aim of the research centres on the meanings people ascribe to specific contexts, without making any association with actions, this danger can be avoided. However, researchers often wish to make links between beliefs and actions. Some studies have concluded that responses to vignettes will reflect how individuals actually respond in reality. For example, Rahman’s (1996) study of female carers’ coping strategies found that, both in their responses to vignettes, and in their recollections of how they had acted in the past, carers dealt ineffectively with conflict. In contrast, Carlson (1996), using vignettes depicting domestic violence, found that most participants replied that they would leave the violent relationship and seek help, although we know from other studies that this is frequently not how victims of domestic violence respond. Hughes (1998:384) concludes that “we do not know enough about the relationship between vignettes and real life responses to be able to draw parallels between the two”. The recent inclusion of vignettes in multi-method approaches may clarify some of these methodological issues by helping to understand the extent to which abstract responses relate to actions in everyday life.” (Ibid.)

Barter, C. and Renold, E. (1999). The Use of Vignettes in Qualitative Research. University of Surrey, Social Research Update 25-25.

The bit “danger in using this technique in isolation” is ironic in self-isolation. I will use these vignettes as a recruitment method for finding participants. It will be for those who want to, once the quarantine and the real threat of contagion are over, connect more IRL and not just online. It will be for those who are tired of only using their minds (and their hands); who want to use all of their body and be present in the places that they go to. I have not decided yet, which method to use after the first step of using vignettes. It will probably be anonymous surveys with questions regarding internet use and its impact on face-to-face encounters. For the next step, I was going to meet IRL and in-person with those interested and sing together or experience music otherwise. After these workshops, I was planning to do another survey with questions regarding the experience. This multi-method approach, online and offline, might be disrupted by Coronavirus and the on-going rule of social distancing. Before coronavirus and self-isolation became acute, I was already looking at virtual choirs. I watched a video of the virtual choir by Eric Whitacre.

This is what it says on Eric Whitacre’s virtual choir’s website:

“The Virtual Choir is a global phenomenon, creating a user-generated choir that brings together singers from around the world and their love of music in a new way through the use of technology. Singers record and upload their videos from locations all over the world. Each one of the videos is then synchronised and combined into one single performance to create the Virtual Choir.”

I was amazed by it. But a virtual choir went against the aim of my project. My focus was going to be on the physical experience of singing in an actual choir. Watching this, nevertheless, felt like an ecstatic, collective experience. But where is the body in this experiment? The body remains slumped and hunched over the device that allows the participation in this virtual choir (and for me, watching this). The present-absent-paradox applies here, because the singer’s bodies are present, but absent in the places they are singing from.

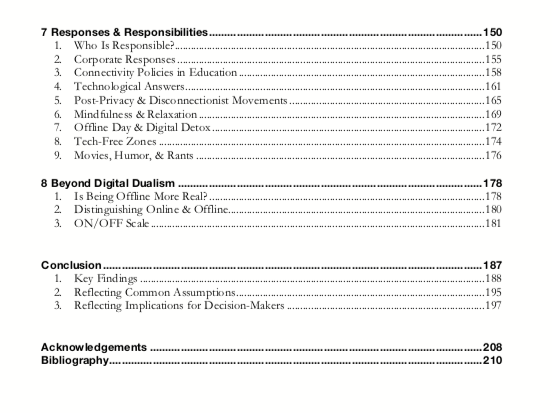

When speaking to friends about this project, they told me about a virtual choir, that was part of the exhibition “24/7 – A Wake Up Call For Our Non-Stop World” here in London, which finished on 23 February 2020 at Somerset House. I have inserted information on the work below from Somerset House website:

“Through the power of humming Melissa Mongiat, co-founder of Daily Tous Les Jours, highlights a metaphysical connection through music.”

REFERENCE: Somerset House Website. Available at: https://www.somersethouse.org.uk/whats-on/247 [Accessed 19 March 2020].

“Melissa Mongiat, co-founder of Daily Tous Les Jours presents I Heard There Was a Secret Chord, a participatory humming channel that reveals an invisible connection uniting those people around the world listening to Leonard Cohen’s song Hallelujah. Real time user data representing the number of these listeners is transformed into a virtual choir – each online listener represented by a humming voice in the space. These sounds are transformed into low frequency vibrations as you start humming along, allowing you to feel a collective resonance. The work is both a scientific and a spiritual experiment, highlighting the metaphysical connection between people on a common wavelength.”

REFERENCE: Audioboom Website. Available at: https://audioboom.com/posts/7471146-artificial-birdsong-and-a-virtual-choir-24-7?fbclid=IwAR13CaGceILMR_HDNHqRyX6qkgl7_LKhiqMTn0uw42CkHzyPFPm5E0m-z5Q [Accessed 19 March 2020].

You can give the virtual humming of Leonard Cohen’s “I heard there was a secret chord” a go here: https://www.dailytouslesjours.com/en/work/i-heard-there-was-a-secret-chord. I would be more than delighted if you wanted to get in touch afterwards to share your experience of virtual humming. Here’s what it says on the website:

“At any given moment, hundreds of people are listening to Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah at the same time. I Heard There Was a Secret Chord creates a metaphysical connection between them through a sensory experience, in an attempt to demystify this universal hymn.”

“Sensory connections: Singing in a group brings about visceral universal emotions, humming, on the other hand, creates a musical vibration inside the body. I Heard There Was a Secret Chord merges the two sensations and provides the public a moment of communal contemplation on the universal, quasi-mystical quality of Hallelujah.”

“The project: The piece consists of a room and a website. Both continuously broadcast Hallelujah’s melody, hummed by a virtual choir. This choir of humming voices is directly impacted by the visitors. Whether they are listening online or in-situ, the number of voices heard increases and decreases as a result of their presence. The fluctuating number is displayed in real time.”

“The website: The website operates like a single-song radio station, fluctuating with the amount of listeners. Anybody can join the choir of I Heard There Was a Secret Chord and feel the universal magic of Hallelujah wherever they are.”

REFERENCE: Daily Tous Les Jours’ website. Available at: https://www.dailytouslesjours.com/en/work/i-heard-there-was-a-secret-chord [Accessed 19 March 2020].

On review, this immersive choir experience differs from Eric Whitacre’s virtual choir in the way that it does involve the body, and it takes place offline, only aided by the online recorded choir of hummers’. Technology serves as an aid to create a metaphysical experience of collective humming, but does not require users to be alone or causes them to have an absent body (Leder, 1990) while making use of it. On the contrary, the body is very much central to this choir-technology experience.

REFERENCE: Leder, D. (1990). The absent body. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Another project I came across, which is also by Daily Tous Les Jours, is called “Giant Sing Along – Outdoor collective Karaoke.”

Here’s what it says on the website:

“Singing in harmony with others–whether in a stadium, around a campfire or in a choir–is the expression of a common emotion. Beyond beautiful voices, the pleasure comes from singing together. Giant Sing Along invites people of all ages and backgrounds to sing their hearts out, karaoke style, sharing in a collective musical experience.”

“The Project: The fun of karaoke is that it doesn’t require skill. This is why Giant Sing Along integrates a sound processing system that lightly auto-tunes the voices, creating a “quasi-professional” choir. (You’re welcome!) The songs featured at each Giant Sing Along event are chosen online by the public. This process involves the local community in the project and guarantees the success of the party.”

“More Together Than Alone: Collective experiences have the power to transform our relationship with public spaces. Beyond its festive nature, Giant Sing Along is an artwork that fosters feelings of belonging to a community through moments of spontaneous, simple joy.”

This second project by Daily Tous Les Jours, too, shows that there are attempts made to create offline, collective, musical experiences. These are designed with the help of immersive technology (here users online choose the songs for offline users) and with the aim to foster feelings of community and simple joy. This shows that there is a demand for or, hence, a lack of collective, offline experiences.

“Finally, future research can also explore whether engaging with online technology changes people’s opportunities to engage in the socioemotional processes that define sociability, such as empathy and perspective taking. In her 2015 book, Reclaiming Conversation, Sherry Turkle (2015) suggested that increased engagement with technology may lead people to immerse themselves in idealized online identities that help them to avoid those in-person and in-depth conversations in which we “allow ourselves to be fully present and vulnerable . . . where empathy and intimacy flourish and social action gains strength” (p. 20). Future research can explore whether online technology alters not only people’s capacity for sociability but also their selection of situations in which they might employ this capacity.” (Waytz and Gray, 2018: 485)

“Technology can help us be more angelic, providing a low-cost way to reach out to others and lift them up. However, by distancing us from tangible emotional signals of others’ suffering, it can also unleash the worst of our demons. Although online technology allows us to help and harm others, it is not inherently good or evil; instead it is likely to reinforce people’s preexisting prosociality and antisociality. Research suggests that technology can supplement sociability in offline interactions—as long as it does not replace face-to-face interaction.” (Ibid., f)

“Online technology is still in its infancy. But as famed futurist Ray Kurzweil (2003) writes, we may soon have “full-immersion visual-auditory environments” and “will be able to enter [them] . . . either by ourselves or with other ‘real’ people” (para. 9). Will these powerful online environments enable us to be more or less in tune with other people’s emotions? Our review suggests that the impact of online technology on sociability may depend on whether online technology enables altruism or spite and whether the interactions it affords enable or disable deeper interactions with others. But most of all, this review suggests that more conclusive research is needed to truly reveal whether online technology makes us kind or cruel.” (Ibid., 486)

This is what I set out to do: a conclusive research that reveals the impact of online technologies on our sociability, and ways to reconnect to our bodies.

In Turin people in self-isolation are sharing a euphoric, musical moment with each other from their balconies:

Transcript:

“Could this reshape the way we interact with each other?”(Asthana, 2020)

“It will reshape our notion of our responsibilities to each other, both kind of really intimate family responsibilities but also responsibilities to your neighbours and your friends. And in the very first instance, even before we talk about rebuilding social connections in a practical way, it just reminds you how much you love them all. And so I think that will be a change and I think, I’ve gotta be honest, I don’t want to make this into a political point but if you look at what first and second world wars did, to our notion of society and what it meant we did the most radical good in history after those wars because we all sustained losses, we all sustained anxiety, and we kind of remembered what mattered. And it was out of that spirit, that we built the NHS and the largest program of social housing we’ve ever conceived. So, I think there is something about a reset in this, there is something just about kind of remembering what matters, remembering what doesn’t matter that makes social ambition hugely possible. […] ” (Williams, 2020)

REFERENCE: Asthana, A. (presenter) in conversation with Williams, Z. (20 March 2020). Today in Focus: Social distancing: learning to cope with a new normal. (00.20.46 until 00:22:05).Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2020/mar/20/coronavirus-learning-to-cope-with-a-new-normal [Accessed 20 March 2020).

REFERENCE: Gill, E. and Randall, L. (20 March 2020). Coronavirus: Hundreds of children sing to self-isolating older residents near school. Available at: https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/coronavirus-hundreds-children-sing-self-21728150 [Accessed 20 March 2020].

REFERENCE: Scully, E. (20 March 2020). Touching moment primary school pupils sing Something Inside So Strong to elderly people isolating in sheltered housing opposite their playground. Available at: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-8134807/Primary-school-pupils-sing-elderly-flats-opposite-playground.html [Accessed 20 March 2020].

” […] Even the language has changed with astonishing speed. “Social distancing”, “self-isolation” and “WFH” [Work From Home] entered near-universal usage in a matter of days, matching the velocity with which personal behaviour had to change. It began with the awkwardness of the rejected handshake, an elbow-bump offered in its place, a practice which seemed novel a mere fortnight ago – and it ends with people sharing a pint by each drinking alone in their homes, but doing it on a screen via FaceTime, Skype or Zoom.” (Freedland, 2020)

“In this new landscape, the only meeting places are virtual, with social media the obvious forum.“ (Ibid.)

REFERENCE: Freedland, J. (20 March 2020). As fearful Britain shuts down, coronavirus has transformed everything. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/20/as-fearful-britain-shuts-down-coronavirus-has-transformed-everything [Accessed 20 March 2020].

“So viel Miteinander war nie. Das Virus bringt uns auseinander und gleichzeitig enger zusammen.” [There has never been as much community as now. The virus keeps us apart and simultaneously closer together.] (Peitz, 15 March 2020).

“Vor allem die Macht der Musik bricht sich Bahn. Krise, Ausnahmezustand, Isolation? Es ist der Gesang, diese alterierte Form des Sprechens und der Kommunikation, auf den viele in dieser besonderen Situation zurückgreifen, ein fast archaischer Akt.” [First and foremost, it’s the power of music that can be witnessed. Crisis, state of emergency, isolation? It is the singing, the altered version of speaking and of communication, many make use of now: It is almost an archaic act.] (Ibid.)

REFERENCE: Peitz, C. (15 March 2020). Singen gegen die Quarantäne. Available at: https://www.tagesspiegel.de/kultur/solidaritaet-in-zeiten-des-coronavirus-singen-gegen-die-quarantaene/25644758.html# [Accessed 20 March 2020].

With events cancelled, organisers offer virtual concerts and operas online. Nietzsche had an ecstatic, collective experience in one of Wagner’s operas. It was from then on that he was not as pessimistic about life anymore as he was before. He found that the experience that makes life bearable is an operatic moment of ecstasy. Although we can’t physically go to the opera at the moment (and maybe couldn’t feel like we could before for financial or other reasons), we can livestream operas for the time being on the following:

https://www.digitalconcerthall.com/de/home

https://www.staatsoper.de/stream/

The Royal Opera House in London is showing online: Peter and the Wolf, The Royal Ballet, 2010 – 27 March 2020, 7pm GMT, Acis and Galatea, The Royal Opera, 2009 – 3 April 2020, 7pm BST, Così fan tutte, The Royal Opera, 2010 – 10 April 2020, 7pm BST and The Metamorphosis, The Royal Ballet, 2013 – 17 April 2020, 7pm BST.

I reckon that streaming an opera online will not come close to what Nietzsche experienced at the opera IRL. Feel free to send me a message about your experience of watching one of the free operas on one of the links or we can try and watch together on with the app Zoom. It should be noted that Nietzsche was not singing himself, he was just watching and experiencing the operatic singing and the acting in front of a stage set. So, we have singing and sound. I will continue this research with quotes on “sound’s invisible, disruptive, and affective qualities” (@The MIT Press. Available at: https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/sonic-agency) examined by Brandon LaBelle in his book “Sonic Agency” (2018):

“Are there modalities of a sounded subjectivity that can support new formations of coming together and in support of emancipatory practices? Sonic Agency sets out to engage the contemporary conditions of social and political crisis by way of sonic thought and imagination. Through the positing of what the author terms “sonic agency,” sound and listening are brought forward as capacities by which gestures of speaking out and coming together are extended.” (LaBelle, 2018)

“Is there a potential embedded in sonic thought that may lend itself to contemporary struggles? What particular ethical and agentive positions or tactics may be adopted from the experiences we have of listening and being heard? Might the knowledges nurtured by a culture of sounding practices support us in approaching the conditions of personal and political crisis?” (Ibid.)

“The gestures that bring us into the world, making us seen and heard, felt and witnessed by others, carry with them an intrinsic forcefulness; we gesture, we move, we impinge onto our surroundings and others. These are embodied actions by which subjectivity gains definition and which produce effects and meanings from their intensities – they make impressions from which certain consequences are generated. These actions, and their repercussions, are formed by and through the interactions and reactions between oneself and others – I am only myself in so far as others shape me, and through which I in turn shape others. The deep and defining relationality of being a subject in the world, however, is in constant tension with given social institutions, with the processes of language and the limits of speech, and through one’s access to support structures, including the extremely important and highly varied relationships of which one is a part. We are not only relating body to body, subject to subject, but equally according to the institutional frameworks that enable or limit contact, movement, and responsiveness. I feel myself with and through others, as well as by entering or exiting the institutions and offices of society – by scraping across the limits and structures of the social order and the permissible.” (Ibid.)

“Relationships, in this way, mostly extend from the personal to the institutional, creating a more entangled and experiential way of being in the world in which moments of exchange, sharing, and feeling are shaped by particular frameworks. In turn, one contributes to those frameworks, demanding entry and participating in their activities, bending the languages and the practices that perpetuate particular institutional orders. From such perspectives, the sensual nuances of feeling and of being felt, of wanting and needing, greatly inflect the actions and gestures that make one seen and heard in public life, and that inform how such visibility and audibility lead to or hinder positions of social and political participation.” (Ibid.)

“Audre Lorde, in her essay on “the erotic,” suggests that it is by way of the sharing of joy that the productive conditions for mutuality and empowerment may be nurtured. As she describes: “The sharing of joy, whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual, forms a bridge between the sharers which can be the basis for understanding much of what is not shared between them, and lessens the threat of their difference.”i Lorde furthers this thinking by arguing for a richer integration of joy and pleasure – our excitements and our vitalities – within the institutional constructs of family relations, community work, and public life. The sharing of joy thus acts as a highly charged foundation from which forms of co-habitation, interpersonal exchange, and mutuality may emerge. Importantly, Lorde poses the erotic as that which acts to bridge the “spiritual” and the “political.” From such a condition, she writes, “we begin to feel deeply all aspects of our lives, we begin to demand from ourselves and from our life-pursuits that they feel in accordance with that joy which we know ourselves to be capable of.”ii” (Ibid.)

“The erotic, the sensual, and the joyful come to act as an empowering basis for putting into practice the intensities central to being a thinking and creative body, specifically by supporting our inherent desire to “share” in such intensities: the erotic is first and foremost a generative project, born from touching and being touched, by the depths of a sensuality that also, importantly, forces us into a state of vulnerability and interdependency. Lorde’s “erotic subjectivity” is one that situates the affective and sensual state of personhood in and around the political, and is thus the beginning of confronting all that oppresses or dominates – that thwarts the full blossoming of life’s vitality – whether in the form of institutional systems or through the internalized fears and anxieties that keep one locked within limited conceptions of oneself and others. The joyfulness of erotic becoming, as the bristling of life with others, ultimately leads to a “visibility which makes us most vulnerable” and yet which is also “the source of our greatest strength.”iii” (Ibid.)

“The experiences of joyful sharing, of the fullness of agency and actions – the activeness of the breathing and feeling body that is ourselves and that flows from us and along with others – such a position supplants theories that would separate politics and the personal and, by extension, the public and the private. In contrast, for Lorde, and for others, in particular bell hooks, whose ideas continually seek to bridge life lived and the formations of public representation (political and other), spaces of political visibility are greatly influenced by the psychological, emotional, and relational passions by which one experiences and desires from the world and others. From such a position, is not the political a space of relations and mutuality served not solely through reasonable deliberation or strategic alliance, but one equally shaped and instituted by what moves this body? By the intimate relationships and emotional knowledges that often sustain communities, and that become central in times of conflict?” (Ibid.)

“bell hooks captures the question of “passionate politics” by arguing for a mode of coming together “in that site of desire and longing” which may act as “a potential place of community-building.”iv hooks is dedicated to steering questions of politics according to the affective lessons of desire and longing, as well as through an ethos of loving relations.” (Ibid.)

“[…] Weakness is not only articulated through abusive forces that may fix one within a system of dominance; rather, it is equally an essential human condition, articulated in moments of crisis, fragility, and loss as well as through “joyful sharing” and the simple instances of feeling oneself touched by another; a vulnerability central to being human. These conditions and experiences may additionally act as the basis for countering systems of domination; following Lorde and hooks, weakness may articulate a performative impasse in which powers of dominance stagger, and from which forms of self-determination and shared resistances may find traction. To let oneself go within the fervor of joyful contact, or to grow limp in the arms of another, a friend or even a police officer when refusing to vacate – this body carried off – or to resist through silently standing still, or holding firm together, these expressions find their strength not only through political conviction, but through a deep appeal to moral conscience.” (Ibid.)

“[…], the counter-culture was a movement in how bodies feel, perceive, and act together. This would give way to understanding how political subjectivity is expressed not solely in gestures of speaking up, or in rational collective assembly, but equally in “arational” formations of energetic attunement, ecstatic togetherness, and affective intervention – formations in which the personal is deeply political and the political is something to be lived and shared.” (Ibid.)

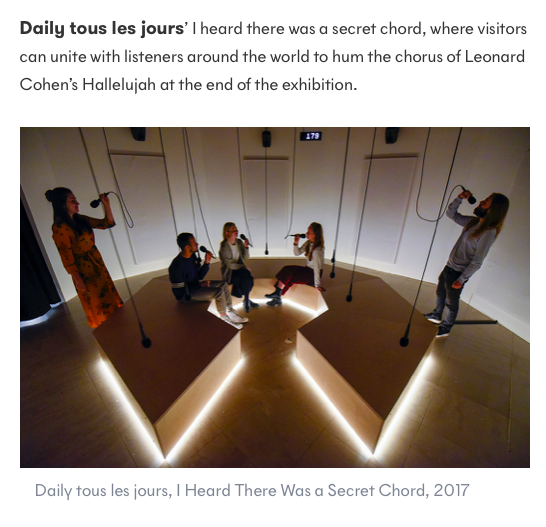

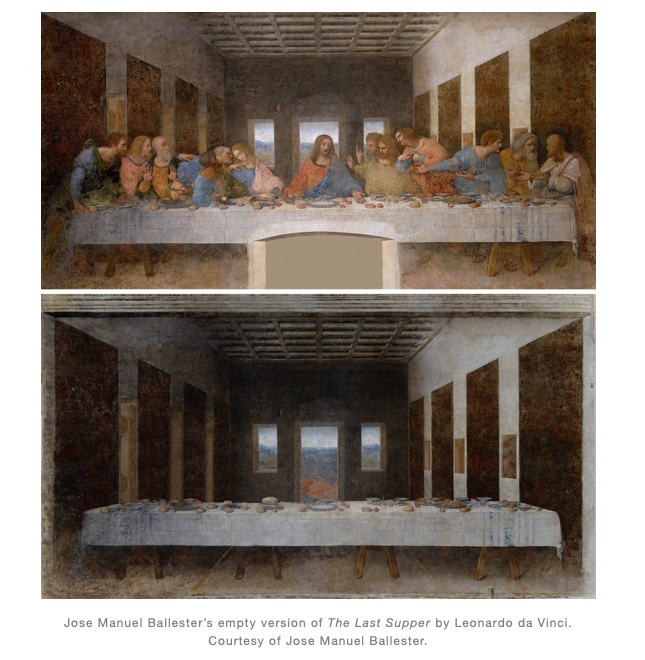

Sharing is a big part of social media. Here are some memes [Meme = A cultural item in the form of an image, video, phrase, etc., that is spread via the Internet and often altered in a creative or humorous way. Definition taken from dictionary.com.] that are being shared at the moment in relation to the coronavirus. Some translate self-isolation into the medium of the image:

In her book “The Lonely City” (2016), Olivia Laing writes:

“As the Whitney curator Carter Foster observes in Hopper’s Drawings, Hopper routinely reproduces in his paintings ‘certain kinds of spaces and spatial experiences common in New York that result from being physically close to others but separated from them by a variety of factors, including movement, structures, windows, walls and light or darkness’.” (Laing, 2016: 17)

On the back of the book, it reads: “What does it mean to be lonely? How do we live, if we’re not intimately engaged with another human being? How do we connect with other people? Does technology draw us closer together or trap us behind screens?”

REFERENCE: Laing, O. (2016). The Lonely City – Adventures in The Art of Being Alone.

I just came across this article when I was looking for information on Hopper’s lifetime to compare it to ours:

“Hopper tapped into the collective consciousness of his time, but inadvertently, he also captured the spirit of 2020 amid a global pandemic […]” (Figes, 2020)

“[…] as one 21st-century Instagram user @alexandraroach1, wrote: “This could be me in the painting, but I would add a phone into her hand…”” (Ibid.)

“The more often it is shared on social media, the more quickly we remember that everyone else is in the same boat. Or in a similar room, somewhere in the UK [or anywhere else], scrolling anxiously through their feed, or pondering the future of human existence.” (Ibid.)

“Let’s be totally honest, loneliness is an unavoidable characteristic of contemporary life, especially when individuals live in large cities. This is why we all have intense addictions to social media – a virtual façade to mask the underlying angst [One may be reminded of Olga Mikh Fedorova’s print on canvas further up on this blog of a boy looking on his phone with the relating title “Protection”.] and another way to find social connection with strangers making witty one-liners on Twitter.” (Ibid.)

REFERENCE: Figes, L. (20 March 2020). How artist Edward Hopper became the poster boy of quarantine culture. Available at: https://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/48442/1/how-artist-edward-hopper-became-the-poster-boy-of-quarantine-culture [Accessed 23 March 2020].

Edward Hopper’s paintings from the 20th century serve as a visualisation of people in self-isolation and quarantine today. They render visible people in the privacy of their rooms. Social media and posting selfies from our homes have long blurred the lines between public and private. However, these paintings are not from the perspective of the subject in the room, but by someone (or something) from the outside, as if the walls consist of glass. The loneliness is exposed. In the current pandemic, everyone is alone in their homes, but, everyone knows that everyone else is alone and separated from friends and other members of the family. So, while people are waiting in their homes, until further notice from their governments regarding rules of self-isolation, they know that others are in exactly the same position, which creates a feeling of solidarity and togetherness. The popularity of the many shared Hopper memes testifies for that.

The public, on the other hand, is (mostly) devoid of people. In a world where we are not allowed outside with the aim to prevent infection and contagion, (not just technology but also) sound is a way of getting in “touch”. Sound can be shared by people from inside their homes, by opening windows, stepping on balconies and seeing each other over the road, just as the world first saw it in Italy.

“Balcony singing in solidarity has been a growing reaction to the coronavirus lockdown in Italy this weekend.” (Thorpe, 2020)

“From the southern cities of Salerno and Naples, and the Sicilian capital Palermo to Turin in the north, residents of apartment buildings and tower blocks are continuing to sing or play instruments, or to offer DJ sets, from their balconies in a trend that is spreading from Italy across Europe to Spain and even to Sweden.” (Ibid.)

“The Italian tune from the 1990s, Grazie Roma, with the lyric, “Tell me what it is which makes us feel like we’re together, even when we’re apart” is also popular online.” (Ibid.)

REFERENCE: Thorpe, V. (14 March 2020). Balcony singing in solidarity spreads across Italy during lockdown. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/14/solidarity-balcony-singing-spreads-across-italy-during-lockdown [Accessed 23 March 2020).